H.G. Lewis, Godfather of Gore

This article originally ran on FEARnet.com September 2011

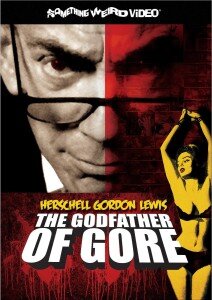

I first discovered Herschell Gordon Lewis at age 13 or 14, when I discovered Color Me Blood Red at the local video store. As is the intent of exploitation cinema, I was drawn to the brazen title and lurid video box. Since that day, I have been a diehard H.G. Lewis fan, and I must admit, I geeked out when I found out I would be speaking to the Godfather of Gore. At 82 years old, he is more cogent and better spoken than a man half his age, and is still making movies. As his seminal gore classics – Color Me Blood Red, Two Thousand Maniacs, and Blood Feast – are released on blu-ray, and a new documentary, Godfather of Gore hits DVD, I got the chance to talk to him about the grindhouse days of yore, how the business has changed, and what his new projects are.

I’ve got to be a fan girl for a minute. I first saw Color Me Blood Red when I was 14, and it was all over at that point.

[Laughs]. So you’re saying I’ve ruined another life!

Absolutely! In the best way possible.

Instead of the Godfather of Gore, maybe they should call me the Corruptor.

How involved were you in restoring your films?

That’s an easy one: zero. All the restoration was by Jimmy Maslon and Frank Henenlotter and Mike Vraney, three names that mean a great deal to me. As I’m sure you are aware, Alyse, the motion picture business is shot through with flim-flam artists and people with no ethics or morals, and I’ve been lucky enough in this respect to be associated with three guys who have those elements in abundance. So whatever Jimmy Maslon says he wants to do with these movies, he doesn’t even have to check with me – he can go ahead and do it. I could never have the arrogance to say I could contribute anything to these blu-rays. That [the films] still exist are something of a miracle!

You’re movies are grindhouse in the truest sense of the word–

I agree! Let me tell you why. When Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez put together a movie that they called Grindhouse, they somewhat missed the point. They’re approach to this was overproduced. That’s not the nature of this kind of movie – not from a production point of view. Yes, throughout my – what I laughingly call “my career” – I would have been absolutely ecstatic – orgasmic! – over having the kind of budget to make the kind of movie I really wanted to make, with the effects that I would have really liked to have. On the other hand, had Blood Feast, for example – which was the progenitor of this whole category – had that been made with star names and extraordinary effects, and camera work that one expects from major company product, Blood Feast would not enjoy what it has enjoyed historically. Because then we could never claim that we invented something. It would have had to be somewhat derivative of other movies.

I’ve watched the Nightmares on Elm Street and the Screams and the Amityville Horrors, and it feels sometimes like they are making the same film over and over and over again. Nobody can say that about my stuff. Every time, we had to live on our wits. You don’t live on your wits by remaking the movie you just made before.

Do you feel like exploitation cinema as you knew it exists nowadays – or even can exist nowadays?

Exploitation has lost some of its luster because the word has been used too wildly, by people who do not understand exploitation. They stick a label on a movie because it’s either low-budget, or has outrageous scenes in it. That’s not the idea of it. Exploitation has to relate to an audience reaction. People don’t walk out on a movie because of a ragged pan or, it has wandered slightly out of sync; they walk out because they weren’t entertained. The most recent example of that is a movie called Creature, which opened theatrically a couple weeks ago, in 1507 theatres. What I would give for all my movies together to enjoy 1507 screens! [Creature] has a record: the lowest grossing film of its type ever. I didn’t know about this movie until I saw the ads in the local newspaper. I said, “Can this be? With a movie like this, with a campaign this foul, can open in so many theatres against the major company product that is opening the same week?” I watched carefully to see what the grosses were – and they were a new low. That whole weekend, they averaged $220 per screen. That was [produced by] Sid Sheinberg, who is a big name in film. I wish Sid Sheinberg and I had had a conversation beforehand. I might have been able to be of some minor value in explaining the meaning of “exploitation.”

Does it seem weird to you that your films are now being released on a high-definition, high-quality medium?

[Laughs]. You bet it feels weird. Weird is not the word! I just wonder if they are looking at the same movie I was making. It is funny, and it is proof that if you live long enough, you become legitimate. When we made these movies, my partner Dave Friedman and I were considered “outlaws” in the movie business. “How dare these people come into this business and make movies like that?” That existed until people began to total up the grosses that these movies were making. Here’s a movie that, in one theatre, could easily gross more than the whole movie cost to make. Nobody can claim that anymore – not Harry Potter, not anybody. So we set a torrid pace, and the result of that was, once the word got out, people came flying in like hyaenas to a carcass. “If these guys can do it, and they have no talent whatsoever, certainly I can do that, too! I can make a better movie.” Which obviously is true. Anybody could make a better movie than I made – including me. In order to do that, you need that key word: budget. Which I didn’t have. Then after a while I realized that budget was a secondary factor to exploitation.

A mistake that many companies make in this business is that they equate exploitation with transmission of their own ego. I never had that problem – I was always apologizing for what we made!

Did you have any idea at the time that your idea for gore films would essentially define the genre, even up to this day?

Well, I knew this, and it was the only thing I needed to know: my intention was not to create a new category of motion pictures. My intention was to make a motion picture that satisfied two areas: one, the major film companies couldn’t make or wouldn’t make it; and two, it would be “odd” enough that some theaters, in their bravery and competitive position (which would always be secondary to the big chains) would play it, and if we had a decent campaign, people would come see it. We didn’t need a lot of [people] because the “budget” was not high enough for us to take a big loss. That’s all there was to it. I guess you could say it was a “cold-blooded business decision.” Throughout my “career” in the exploitation film business, my decisions were always based on “business” – that’s why we call it the film business. People look at it too personally, too subjectively instead of objectively. I never had that problem. Let’s just grind something out.

The key has to be the campaign. Any schmuck can aim a camera. That doesn’t require talent; we see that all the time. Now, of course – and maybe I started part of this – anyone with a digital camera is making a feature.

So I have you to blame for that!

[Laughs]. Well, I guess “blame” is a better word than “credit.” By this time, somebody else would have done that. But the one thing that I did professionally was that every one of my movies – every one until the most recent one – was shot on 35mm color film with a big Mitchell camera. So that on the back row of a thousand-car drive-in theater, people could see a bright, clear image that wasn’t wobbling all over the place. My prediction is that five or ten years from now, 35mm color film will be a dinosaur. We’re already seeing this in some theaters. Instead of some burly guy coming in on a Friday morning with a new can of film, and hauling out the old one, the projectionist gets his images from satellite. All he does is delete what he has been showing, and download next week’s movie. My new movie, which I just finished, was shot with this big, beautiful RED camera.

Tell me about what you just finished shooting. How has the process changed?

Back in my “glory days,” our principal set of outlets was the drive-in. Now they have become nothing but a place to go for flea markets. The whole category doesn’t exist anymore. There are only a handful of drive-ins left, and everyone is fighting for playing time. I can no longer just say to some buddies of mine, “Hey, play my picture,” which was all there was to it in those happy days. Back then, if only a handful of theaters played my movie, I was off the hook from the viewpoint of investment versus income. Today, it’s a different kind of world. I guess the word is “cluttered.” I go into a video store or I get something from Netflix – a whole bunch of my stuff is on Netflix – and here are titles that I’ve never heard of. But Netflix has them. And of course, now Netflix is dismantling itself into two different categories: one streaming, the other by mail. Again, there is more clutter. And clutter is the enemy of position in the movie business. We’re all subject to it.

You’ve never tried to hide the fact that you started making movies purely to make money, but do you feel any nostalgia for your heyday, especially since the cleanup of 42nd Street?

Yeah. I hated to see 42nd Street get cleaned up, but I’m not sure it totally is. 42nd Street was always a very good bastion for my kind of stuff. Among other things, I could stand there and get a great idea of the flavor of theater-goers relative to the movie I had just put in there. It was a wonderful litmus test for a movie because it was heartless – that’s where you get information! You don’t get it from the major film critics who say what crap [your film] is, and how dare they turn this loose on the unwitting public. That’s the kind of thing you don’t even bother defending yourself against, because they are in an arena that you don’t even want to get into. They are talking about awards… so what? There is one way to keep score in the movie business, and that is: dollars in versus dollars out. Anybody who looks at it from any other viewpoint, I welcome as a competitor.

Can you tell me about this film you just finished?

It’s called The Uh-Oh Show. I’m trying to move this industry in a somewhat oblique direction that I regard as sensible. That is the welding together of the classic splatter film with a comedy. As somebody looks at The Uh-Oh Show, that viewer – who is not part of my family, somebody who doesn’t have any idea of who I am and what am doing – will say, “Hey, that was entertaining!” They will know the whole thing is a big gag. That may bring to our kind of movie people who wouldn’t normally look at it.

The Uh-Oh Show is about a quiz show called “Uh-Oh” and if someone gets a question right, they get every kind of wonderful prize imaginable: a Mercedes-Benz 600, a trip around the world, a million dollars a year for the rest of their life. But if you get it wrong, the maniacal emcee says “uh-oh…” He will ask a question, for example: “What was president Woodrow Wilson’s first name?” The contestant senses a trap there, but she can’t figure out what it might be. The clock is ticking… she hesitantly says, “W-w-oodrow?” “Uh-oh!” says the audience, and the emcee says, “Too bad. Woodrow Wilson’s real first name was Thomas.” She didn’t get it right, so out comes this gigantic guy with this big radial saw – he’s called Radial Saw Rex – and wham! Off comes her left arm at the shoulder. Typically, in the classic splatter film, she would die of blood loss and shock. Not in The Uh-Oh Show. She’s annoyed. The emcee comes out and asks her if she wants to come back next week, “There are still all these prizes to win!” And she says, “Yeah, I’ll come back!” The next thing one sees is a man in a filthy workman’s costume with a hammer and a great big spike, and he is hammering this shredded black arm onto her shoulder. She’s standing there, annoyed. “Wait a minute, that’s not my arm. And you’re putting it on backwards!” He says, “Look lady, this ain’t the Mayo Clinic.” That is the tone of the entire movie. I am counting on people being convulsed with laughter.

I’m talking out of school to you here, because I sense I have a kindred spirit. I wrote this movie and I directed it, but I have not been involved in the distribution of it. In my opinion, the producer of this movie has handled distribution in a totally amateurish way. He is bypassing any possibility of a theatrical release in favor of a company called Media Blasters – and I’m giving you their name because I am not their fan – they will put The Uh-Oh Show in their catalogue, and that is where it will sit, rotting away, in case someone wants to buy that DVD. So they have no exposure at all; it’s just something else in their catalogue. That was not the intention I had when I made that movie. It is just now going into release.

How did it happen like that? How long as the movie been finished?

It was only three weeks ago that it went into the Media Blaster’s catalogue. I’m out there pitching another movie called Mr. Bruce and the Gore Machine and believe me, with this one, I am not going to sign an agreement excluding me from distribution. That was a mistake I made with The Uh-Oh Show. I can only hope that someone will rectify that mistake. There again, the success or failure of a movie is based on distribution. That is the key.

Please tell me about Mr. Bruce and the Gore Machine – that sounds fantastic.

Again, it is a combination gore film and parody. So again, we can attract people who don’t normally go to see this kind of movie. [Mr. Bruce] is someone who replaces overblown, too-fat legs and limbs and so on, with stainless steel. We have a character in there, who regards herself an actress, whose first name is a famous European city, and her last name is a chain of hotels. We have a character in there called London Sheraton. Again, the whole thing is a parody, and I am counting on that being a little more of a commercial enterprise than The Uh-Oh Show.